If you spend a good amount of time in manga circles, you may have heard the term dōjinshi before. And you may have certain assumptions about what it is, which I fear is quite common, particularly for those in the west. But for those who’ve ever been curious about dōjinshi and want to learn more about the medium, here is a quick and easy guide to what it actually is, where to find it, and even a few recommendations!

What Is Dōjinshi?

The term “dōjinshi” is derived from the Japanese word “dōjin,” which literally translates to “same people” and refers to a group of people sharing a common interest. The word has also come to refer to self-published creative works made by such groups of people, and include dōjin anime, dōjin music, dōjin games, and dōjinshi. With the added suffix “shi,” which refers to printed publications, dōjinshi encompasses the entire category of self-published print works.

It is a common misconception that dōjinshi is equivalent to (mostly erotic) fan fiction. And while there are many dōjinshi that do fall into this category — especially given the fact that self-publishing means there are no restrictions from publishers on content — it is certainly not all that dōjinshi is. Alongside all the dōjinshi that is based upon existing characters and stories (this category of dōjinshi is also known as aniparo), dōjinshi also includes plenty of completely original work. It is also important to note that dōjinshi is not exclusively created by amateur creators. Many professional mangaka got their start in dōjinshi, and some even continue to participate in the practice in addition to their official projects.

It first emerged as early as the Meiji period, in the 1870s and 1880s. Often created and distributed within small groups, it reached a peak during the prewar years of the Shōwa period as a popular vehicle for creative expression among young people. Though the prevalence of this category has experienced various rises and falls throughout its history, it has grown increasingly popular since approximately the 1980s when aniparo became a more predominant part of the market, and with the founding of Comiket — an event dedicated specifically to dōjinshi and now the largest comic convention in the world — in 1975. Today, with the rise of technology and ease with which creators are able to not only create, but also promote and distribute their own work, dōjinshi has expanded even more significantly.

Where Can I Read Dōjinshi?

The hard truth is that it is not particularly easy to legally access it in a way that allows you to support the creators, especially for English-language readers. Of course, there are definitely some that are licensed in English, but it can involve quite a bit of digging to find them.

A couple resources I’ve found where readers can get their hands on some dōjinshi in an official capacity are Star Fruit Books and LILYKA, two small English language manga imprints. Star Fruit Books distributes both traditionally published manga and dōjinshi, and LILYKA specializes in yuri manga, working specifically with dōjinshi artists to distribute their work.

Dōjinshi Picks to Get You Started

Sometimes works that start out as dōjinshi get acquired by publishers or receive adaptations, giving them more exposure, and more of a chance to become licensed in English. Here are just a few dōjinshi that went this route, some of which are on the more easily-accessible side, for readers to check out if they are interested in exploring dōjinshi more.

Afro Samurai by Takashi Okazaki

Probably most well-known for the anime series (and its sequel) starring Samuel L. Jackson, Afro Samurai was originally published in the magazine Nou Nou Hau. Following the release of the anime, the creator Okazaki recreated the manga, which was then published in English by Seven Seas and Tor. The story takes place in a futuristic version of feudal Japan and follows Afro Samurai on his journey to avenge the death of his father at the hands of the outlaw Justice.

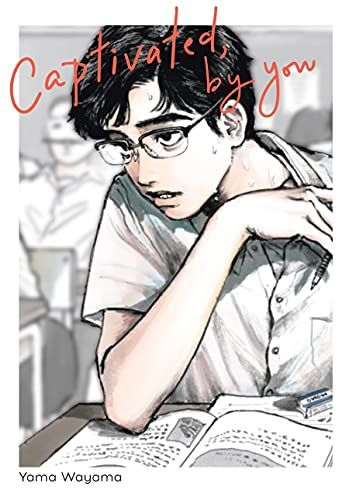

Captivated, by You by Yama Wayama

Captivated, by You was originally released in early 2019 as a dōjinshi, but was acquired and published in a single volume by the seinen manga magazine Comic Beam’s editorial department later that same year. The manga is a collection of interconnected stories about the students at an all-boys school, focusing on two students in particular. Hayashi is carefree and unapologetically himself, while Nikaidou has painstakingly crafted a gloomy persona in order to keep others at bay.

If you enjoy Wayama’s work, also check out Let’s Go Karaoke!, another of hers that was also later acquired and released by a publishing company. This one is a comedy about a member of the yakuza who asks the head of a high school choir to coach him in singing.

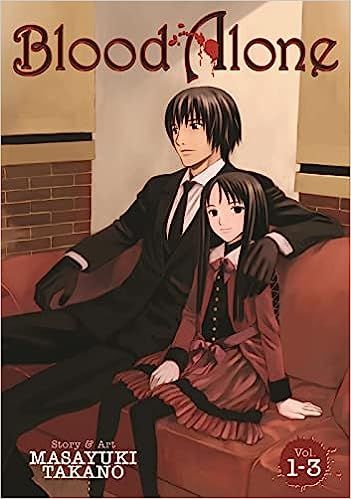

Blood Alone by Masayuki Takano

Starting out as a dōjinshi, BLOOD ALONE was later picked up for serialization. After moving through a couple different publishers, it circled back around to dōjinshi, where Takano was able to give it an ending. The story follows a young vampiress coming to terms with her new circumstances, and the former vampire hunter who acts as her guardian.

Seiyu’s Life by Masumi Asano and Kenjiro Hata

Alright, so this one is not actually licensed in English, but the anime adaptation is available to watch on Funimation. The dōjinshi itself is a slice-of-life yonkoma series that was released over the course of six years at Comiket. It was written by Masumi Asano, a voice actress, and centers around a group of three friends as they navigate the industry as rookie voice actors.

Beyond just dōjinshi, it can be tough to figure out which of the many resources to trust when you’re trying to get your hands on manga without accidentally getting involved with piracy and scanlations. We’re here to help, with these great manga readers and apps, plus the best manga websites, to help you get your fix and keep up with what’s going on in the manga world! And, as always, make sure to check out our entire manga archive for all our recommendations and more!